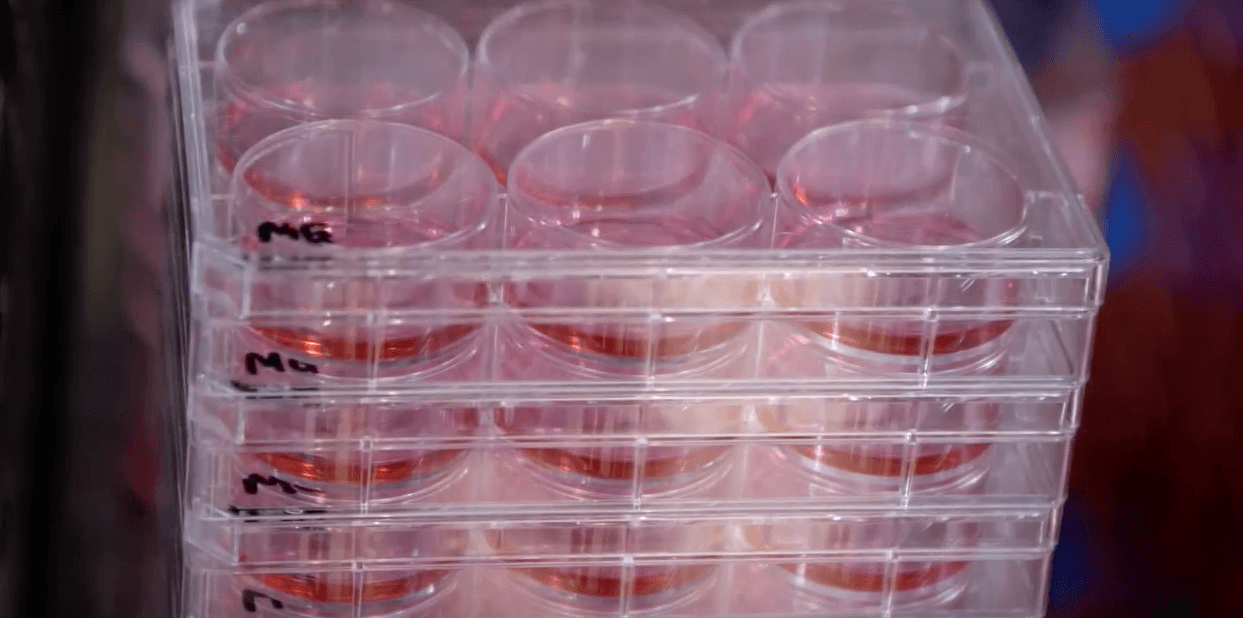

On Monday the world’s first lab-grown, in vitro burger was cooked and eaten in London. Professor Mark Post from Maastricht University, along with his colleagues, took adult stem cells from a cow and then turned them into strips of muscle, which they combined to make a beef patty. Some have dubbed the patty, the ‘Frankenburger’.

Post was one of the lucky few who got to sample this artificially grown burger. He said the meat “tastes reasonably good”, but that it did not completely taste the same as any normal beef burger. This could be due to the lack of fat. Another taster, food-critic Josh Schonwald, said “the bite feels like a conventional hamburger” but that the meat tasted “like an animal-protein cake”. It was also described as being a bit dry. It seems then that more work needs to be done. In addition, this method of producing meat is also not commercially viable yet – the two-year project which brought this burger to the kitchen cost £215,000.

The world’s first lab-grown burger has sparked debate about its ethical implications. Prof Post has said: “We are doing [this] because livestock production is not good for the environment, it is not going to meet demand for the world and it is not good for animals.” Indeed, he seems to be correct on these three points. Livestock production is one of the leading contributors to greenhouse gases, the depletion of the rainforest and other forms of environmental destruction. A study published in the Environmental Science and Technology Journal estimates that lab-grown beef would use 45% less energy, produce 96% fewer greenhouse gas emissions, and require 99% less land than farming cattle. It is no surprise then that environmentalists are supporting Prof Post’s innovation.

Cloning meat in the lab, once the method was refined, could be a much easier and cheaper way to produce meat. Prof Tara Garnett, head of the Food Policy Research Network at Oxford University, said that this would go a long way to resolving the global hunger crisis, whereby 1 billion people are unable to meet their nutritional needs. Not to mention the fact that the world population is rapidly growing, making it increasingly difficult to meet the world’s hunger needs.

‘Test-tube’ meat has also received a great deal of support from those concerned about animal welfare. PETA, for example, have backed it, with a statement saying, “[Lab-grown meat] will spell the end of lorries full of cows and chickens, abattoirs and factory farming.” Of course, this is only true if lab-grown meat became the norm. Already people are reacting to this development with immediate revulsion and disgust. But if it did become the norm, this would certainly reduce the suffering (both psychological and physical) felt by billions of farm animals each year. In regards to the “yuck” response that people have had towards cloned, lab-grown meat, I don’t see why it is any more disgusting than consuming beef which came from a cow that suffered its entire life, lived in its own (and others’ excrement), possibly lived among disease, and then killed in a way which most people would not feel comfortable doing themselves.

The famous animal welfare philosopher Peter Singer also wrote a piece in The Guardian on this issue. He wrote:

My own view is that being a vegetarian or vegan is not an end in itself, but a means towards reducing both human and animal suffering, and leaving a habitable planet to future generations. I haven’t eaten meat for 40 years, but if in vitro meat becomes commercially available, I will be pleased to try it.

The ethical arguments in favour of lab-grown meat seem compelling. So why are there critics? Mark Post used stem cells extracted from muscle tissue from a cow that had already been slaughtered. It’s not as if any extra animal suffering was caused in the process. However, animal rights campaigners maintain that lab-grown meat still involves the exploitation of animals – after all, the muscle tissue does have to come from a cow in the first place. Even if the large-scale production of lab-grown meat eradicated livestock farming, cows would still need to be used. Yes, overall suffering would be greatly reduced, but from an animal rights perspective, animals would still be treated as property and exploited, a state of affairs which cannot be justified. The animal rights philosopher Gary Francione is against in vitro meat for this reason. On Facebook Francione responded to Singer’s article in The Guardian:

It is sad that Singer does not use his position to make clear that consuming animals cannot be justified morally. But then, he does not believe that. Indeed, this article rather clearly shows that Singer does not see killing animals as fundamentally unjust.

For Francione, the fact that non-human animals are sentient means that they should never be used as a human resource.

In the process of growing meat in the lab, Post and his colleagues had to use fetal calf serum as well; a further reason to suspect that animal exploitation is involved. However, although the animal rights approach is strictly abolitionist (supporting an end to all animal use), if stem cells could be used without exploitation and suffering, with the potential to abolish livestock farming, an argument could be made in favour of this. In a similar scenario, would it be wrong to use muscle tissue from a dead person in order to prevent massive amounts of suffering? It is still an issue which needs to be debated – it is not so obviously black and white.

Other critics of lab-grown meat argue that eating less meat would be an easier way to tackle meat shortages. Following this logic, it could also be said that adopting a plant-based diet would be the best option. It would be the most effective way to meet the nutritional needs of a growing population, it would resolve world hunger, it would carry far less of an environmental impact than lab-grown meat or eating less meat, and, if a vegan lifestyle became universal (sure, it’s unlikely) then the use of animals as property would be abolished completely.