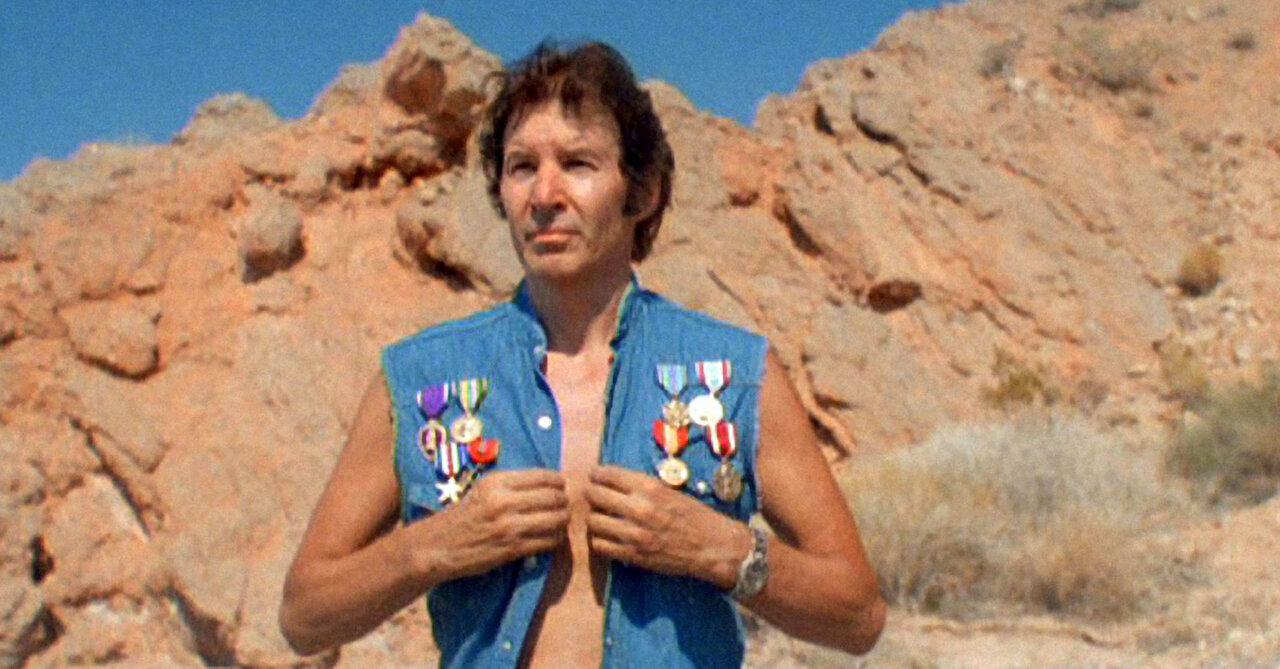

Neil Breen in Double Down (2005)

Part of what makes bad movies (here I mean ‘so bad it’s good’ movies) appealing is the sincerity with which they are created. The directors sincerely believe that their choices, and the resulting film, are good, in a conventional sense, and artistically serious. We can contrast this intention and belief with the perspective of the bad movie lover (like myself) who appreciates the film for the opposite reason: it is good in a non-conventional sense, and I enjoy it because of the ways in which it is perceived as artistically non-serious.

In my review of philosopher Matthew Strohl’s book Why It’s OK to Love Bad Movies, I introduce the concept of the aesthetics of failure. The sense of failure makes bad movies aesthetically valuable, in a very unique way (since we normally judge the aesthetic value of films based on the ways they succeed in various respects – acting, dialogue, plot, themes, cinematography, set design, and so on and so forth – and we typically disvalue the ways in which these aspects fail in films).

The appreciation of bad movies, however, has to come from a particular kind of failure or a sufficient degree of it. If a movie is bad but not bad enough, then it is just conventionally bad and can’t be good in the final sense, to use Strohl’s argument. But if it is extremely bad, or glaringly bad in a multitude of ways, then its conventional failings can make it ripe for enjoyment, humour, and bonding through communal watching. Thus, it becomes good in the final sense.

Tying in the point about a director’s failed intentions and perceptions and the aesthetic value of such failings, I believe we can present an aesthetics of narcissism. More specifically, there can be something aesthetically valuable about a director’s narcissism failing or becoming clear and naked to the viewer. Nevertheless, this appreciation of narcissistic failure, like the appreciation of bad movies, has to be of a specific kind or degree. There needs to be a clear and obvious mismatch between the director’s intentions and perceptions and what the viewer sees on screen. This mismatch lends itself to absurdity, which bad movie lovers value. There is a kind of slapstickish failure of narcissism, where the director’s high sense of self-importance falls flat on its face, and this lends itself to comedy.

Let’s take a look at some examples of where narcissism is most evident, particularly in those cases where film directors who as auteurs (whose complete control over the film leads to unintended disaster and unique success, rather than intended and conventional success). I will then contrast appreciation of this aspect of bad movies – Bad Movie Love – with the opposite attitude: Bad Movie Ridicule.

Tommy Wiseau and The Room

The most obvious example would be The Room (2003). This film was written, produced, and directed by – and stars – Tommy Wiseau. This auteur of the most iconic and well-known bad movie ever made was highly controlling in the making of the film. He berated and publicly humiliated actors and crew members, often arrived hours late to set, struggled to remember his own lines, and refused to pay for air conditioning or water bottles. Greg Sestero, who plays Mark in the film, reveals this about Wiseau in his book Disaster Artist: My Life Inside The Room, the Greatest Bad Movie Ever Made (2013), which was turned into a film, The Disaster Artist (2017), starring James Franco, Dave Franco, and Seth Rogen.

Wiseau’s narcissism shows in many ways: he refused to let Sestero miss a day of filming when he landed a small TV role on the sitcom Malcolm in the Middle, out of envy; he’s convinced he’s a genius; and he lacks self-awareness. And he behaved on set as if he were the only person who existed. In The Disaster Artist, James Franco (who plays Wiseau), presents the auteur as vain and manipulative, while still portraying his oddness and eccentricities that fans of The Room admire.

So you have Wiseau as a person – his personality which shines through his vanity project, The Room – and then you have the viewer’s experience: an earnestly made film being enjoyed as an absurd comedy.

The Films of Neil Breen

I think no films quite reveal the hilarious failing of narcissism more brilliantly than in the work of Neil Breen (whose fans lovingly call his films works of Breenius). Breen has written, directed, independently produced, and starred in six low-budget films. His most well-known (and best I’ve seen so far) is Fateful Findings (2013). While bad movies often stand out for their flat and unconvincing dialogue, Breen excels in this respect, and you have some truly stellar NPC-like scenes in his films.

The reason this bad movie auteur is so often called narcissistic or an egomaniac is that in films like Fateful Findings and Double Down (2005), he plays protagonists who are extremely covert, intelligent, skilled, tech-savvy, and able to single-handedly take on government and corporate corruption (in Fateful Findings) and terrorist forces (in Double Down). Of course, there are conventionally good films that depict powerful lone individuals and geniuses – these are the heroes (if they’re a force for good) we like to see on screen. However, in the case of Neil Breen’s films, Breen’s narration about how impressive and smart he (I mean, his character) is constant. And it’s completely unconvincing and ridiculous.

The protagonists played by Breen ‘use’ multiple laptops and phones (they’re not turned on), and he uses plenty of jargon (with no substance). There is absolutely no way to take the intended seriousness of this character and his actions seriously. I mean, consider the fact that in Double Down, his character’s whole diet consists of canned tuna, eaten straight from the can, which in one scene he clumsily spills all over himself while eating and driving. His films actually go beyond displays of egomania and evince something more like a messiah complex: how a lone wolf genius can save the world.

Craig Denney and The Astrologer

An overlooked, hidden gem is The Astrologer (1975), which like Breen’s films, is a vanity project. There are conflicting reports of whether the movie was ever officially released, likely due to its liberal use of copyrighted music (the rights to the playlist of Moody Blues and Procol Harum used throughout the film weren’t properly secured). It was lost until the American Genre Film Archive recovered it in “a batch of 1,000 pornographic prints”, and a successful Indiegogo campaign in 2014 resulted in the film being digitised. As of today, the film is available to watch on The Internet Archive. It has since become a cult film. Clint Worthington of The Spool wrote:

it can be easy to miss that feeling of discovering the diamond in the rough, that transcendently bad movie you only share with a few people you know through hushed whispers and traded bootleg tapes. Fear no more: thanks to delusional auteur Craig Denney, the diligent efforts of the American Genre Film Archive, and The AV Club and Daily Grindhouse’s lineup of midnight showings at the Music Box, you can get that luster back with Denney’s transcendently terrible fantasy-drama The Astrologer – a film that’s as good a case as any for the value of keeping a little bit of mystery in your moviegoing experience.

The Astrologer is like Citizen Kane (1941) meets The Room/Neil Breen. Starring, written, directed, and produced by Craig Denney, it tells the story of Alexander (played by Denney), who is running a con game at a circus as a psychic; he eventually amasses immense wealth and power by creating an astrological broadcasting empire. It’s a rags-to-riches story, which then becomes Citizen Kane-esque in its narrative arc by showing the rise and fall of this internationally famous astrology media mogul. Jim Vorel in an article on the film for Paste Magazine, writes:

To look at the guy, you’d simply accept that he appears to be an average, somewhat dopey-looking member of 1970s white male society, but man, Denney had some ambitions in him. He seems to have viewed The Astrologer as nothing less than the linchpin to an effort that would catapult him into Hollywood stardom, and the film treats his character with dramatic parallels that are positively Faustian. It’s difficult not to be immediately reminded of the likes of Tommy Wiseau, in terms of how sincerely (but ineptly) Denney approaches his task as both an actor and filmmaker.

The Astrologer is meta in more than one way: in one sense intentional and in the other sense, unintentional. First, in a meta movie-within-the-movie moment, Alexander puts out a movie about his so-called psychic powers and tall-tale exploits, which becomes a $145 million box office smash, cementing his ambition and allowing him to become a celebrity figure. This becomes even more meta if Denney imagined that this film – the actual film, The Astrologer – would also lead to his meteoric rise towards stardom.

The unintentional self-referential nature of the film is that Denney’s ambition fails, just as Alexander’s does (failing in both business and personal matters, leaving him a broken man). The Astrologer was perhaps never officially released and fell into obscurity; so the film had all the ego and ambition (like Alexander) but none of the success, at least not in any monetary or conventional sense. There was the fall, but never the rise. The aesthetics of narcissism in The Astrologer are created through Denney’s vanity and the blandness in acting and line reading we see in the film.

While information about Denney is scant, given how obscure his film is, Sean Welsh of Glasgow’s Matchbox Cinema Club tells us:

His [Denney’s] publicist, Dustin Paul Milner, claimed Denney was “booted out of every school he ever attended and was fired from all 17 radio stations he worked for in a seven-year broadcasting career, as a “top 40 radio personality.” This was before he made the leap into “the astrological charts business” in 1968, when he was around 25. Within ten years, he’d be a “self-made” millionaire and, wait for it, “one of the youngest studio heads in Hollywood history”. He’s described by friends as loyal, obsessed, generous and brilliant.

If true (the veracity of these claims is uncertain), then it is even more clear that The Astrologer is a complete vanity project, revealing one more way in which the film is meta. Welsh describes Denney’s company Moon House as “a computerized horoscope service which, for a price, whips out detailed astrological forecasts for individuals and corporations,” and by 1975, Denney claimed to have made $31 million as a result. Nonetheless, Denney’s friend and associate Arthyr Chadbourne (who plays business manager Arthyr in the film, speaking to self-referentiality again) has suggested at LA screenings/Q&As that Denney was notorious for exaggeration and self-aggrandisement. Chadbourne reportedly said, “Craig was wonderful with hype. Everything was millions … you should read some of the things we used to send out to investors.”

Claudio Fragasso and Troll 2

Italian horror director Claudio Fragasso wrote and directed Troll 2 (1990), under the pseudonym Drake Floyd, which has become a cult classic bad movie, with its fandom – and the lives of its actors in the wake of the film’s cult success – portrayed in the documentary Best Worst Movie (2009). Fragasso, whose English was quite poor at the time of filming, hired an Italian, English-challenged crew to work on the film. Michael Stephenson (who plays the son, Joshua Waits in the film) told Vice in 2021:

I don’t think I really processed it as a kid, but looking back at the script now it’s translated very strangely. If I was even a few years older I’d have read it and been like, ‘What on earth? This doesn’t make any sense.’ It’s like auto-Google Translate or something in today’s era. It almost created this new language, like an Italian’s interpretation of what American teenage kids would say.

Stephenson said elsewhere in the interview with Vice:

There’s no sense of irony in it at all, and that’s refreshing. You can feel the heart of the filmmaker at its core. There’s somebody behind this who was really trying to make a great movie. It’s still an eminently watchable film, but it makes no sense and there are all sorts of logic flaws and the effects are terrible and the acting is weird. It feels like aliens made it on another planet as a representation of what they thought humans acted like.

Indeed, in Best Worst Movie, Fragasso unwaveringly maintains that he made a (conventionally) great movie and that he’s proud of it. His lack of self-awareness is completely at odds with why fans of the movie adore it so much, and in the documentary, we see Fragasso have an outburst at a cast Q&A because he doesn’t like hearing about the ‘alleged’ language barrier and he is exasperated about the way everyone is poking fun at his movie. So despite its success as a cult classic, Fragasso doesn’t embrace the clear failings that have made it such a success in this respect. Bill Gibron, in an article for PopMatters, highlights Fragasso’s sense of self-importance, as shown in Best Worst Movie. He writes:

On the scary side of things is Fragasso himself. Along with wife and creative partner Rossella Drudi, he argues about the film’s earnest and “intelligent” subtext, suggesting that his vision was too forward thinking for a 1990 audience. Indeed, he chalks up the resurgence of Troll 2 not to post-millennial irony run amuck, but a deep appreciation for his masterful, well meaning message. As he becomes part of the process, as he joins the rest of the reunion for screenings and Q&A sit downs, Fragasso starts to doubt his own conclusions. Before long, he turns belligerent, arguing with the actors as they address friendly fan inquiries and yelling relentlessly during supposed cheery nostalgic scene recreations. He eventually labels everyone “dogs”, inconsiderate of his place in this weird multimedia pecking order.

We can contrast this reaction to the trajectory of the film with George Hardy (who plays the dad, Michael Waits), who is endearingly upbeat and affable and has no regrets about the film. He doesn’t complain about how he never made it as an actor and ended up a dentist instead. And he embraces the ‘so bad it’s good’ status that Troll 2 has earned and the cheers and adoration he receives at screenings.

Fragasso is the party pooper while Hardy takes on much more the attitude of the bad movie lover. And this brings me to the final idea I’d like to discuss.

Bad Movie Ridicule vs Bad Movie Love

In Why It’s OK to Love Bad Movies, Strohl distinguishes between Bad Movie Ridicule and Bad Movie Love, a distinction that matters when we talk about the aesthetics of narcissistic failure in ‘so bad it’s good’ movies. In my review of the book, I point out that bad movie ridicule:

is a posture of mockery, disdain, and schadenfreude; it treats bad movies – as well as the people who created them and the people who sincerely love them – as worthy of contempt. The ridiculers may enjoy making fun of these films, but they still see them as bad in the final sense (aesthetically disvaluable). Bad Movie Love, in contrast, judges certain bad movies to be aesthetically valuable, “in part because it’s bad in this limited sense” (p. 4). Strohl stresses, throughout the book, that the stance of Bad Movie Ridicule is inferior to that of Bad Movie Love; the former is less fulfilling, both in terms of living an aesthetically rich life and in terms of the connection with others it offers.

Strohl appeared to discuss his book on the philosophy podcast Overthink and co-host Ellie Anderson presented the following critique:

You set up a distinction between love of bad movies and ridiculing bad movies in the book, you say in the book, that bad movie ridicule is enjoying a movie at its own expense, by mocking it for how it violates conventional norms. Whereas bad movie love is precisely appreciating a movie because it violates conventional norms. And I was thinking a lot about this distinction because for me personally, I feel like they’re not as distinct as you suggest in the book, and you know that they do often overlap in practice, but you think that they are in principle, distinct attitudes toward bad movies.

She offers the example of the 1976 sci-fi film Logan’s Run, which she found entertaining to watch and loved how hilarious and unrealistic the set designs were, given that the film was meant to be showing a futuristic city. But she said, “I don’t feel like my love of it was actually distinct from ridiculing it.” In response to this, Strohl said, “I think there’s something that is like ridicule adjacent that’s not ridicule,” which he calls “a kind of like rhetorical game of playful mockery.” One can playfully mock a film in the spirit of appreciation, enjoyment, and seeking to find what is interesting about the film, whereas ridicule, Strohl claims, is not about “trying to uncover what’s outside of the bounds of convention we can find admirable about this.” Instead, it is a standpoint of “presumed superiority” and laughing – crucially, from a place of contempt – at the filmmaker and everything they’ve done ‘wrong’. They’re viewed as idiots, rather than as creative and unintentionally comedic.

Connecting this to the narcissism of bad movie directors, we can say that the aesthetics of narcissism and failure come from a place of appreciation; one is glad that the director had such high hopes and vanities because it was precisely that mindset that produced the final result: a bizarre and surreal film that can be continually enjoyed and creatively engaged with (such as watching it with a group of people, each of whom can point out interesting aspects one may have missed when watching it alone).

The narcissistic elements that go into certain bad movies also add to the aesthetic value of the films because, as already stated, it creates an entertaining mismatch between artistic intention and the final result and viewer experience. The contrast between the earnestness of the director and the resulting ridiculousness on screen is, moreover, extremely human. Such failings are embraced, not sneered at. Moreover, it is impressive and thought-provoking that these films can induce such strong feelings of cringe. This may reveal something important about social norms and the human condition (see my essay on the value of cringe).

Bad Movie Love can be an attitude of playfully mocking the narcissism and failure we see on screen, which Strohl argues is adjacent to Bad Movie Ridicule, but which is certainly not at all that far from affection. Perhaps this is culturally dependent to a certain extent, however. Since I’m British myself, ‘taking the piss’ out of other people is the norm, and it’s usually your closest friends and loved ones you will do this most to, and most ruthlessly. It’s playful mockery. It’s a way of deepening relationships, by not taking oneself or each other too seriously, and finding any opportunity for laughter, which bonds us like social glue. So we can take the piss out of bad movies and the directors behind them in this sense. Fans of Neil Breen, for instance, do exactly this.

Narcissism is human. Failing is human. And when narcissism fails, there can be something gratifying about it, something justified about it – an inflated ego has been put in check. But when it comes to ‘so bad it’s good’ movies, such narcissistic failure is not viewed in a moralistic and judgemental sense; it is seen as part of the aesthetic fabric of the film. While Wiseau’s personality and practices as a director may not be morally acceptable, this does not mean we should gloat about how his sincere aims for The Room failed to materialise. Instead, the posture of Bad Movie Love means that the mismatch between the director’s ideas and reality becomes a source of genuine intrigue and joyful comedy, which enriches one’s life. It is through such narcissism and failure that bad movies are able to breach received norms in novel ways.

We should be grateful for all the directors mentioned here, who were unafraid to chase their ambitions, and who were unaware of the reasons why their work would be loved by so many.