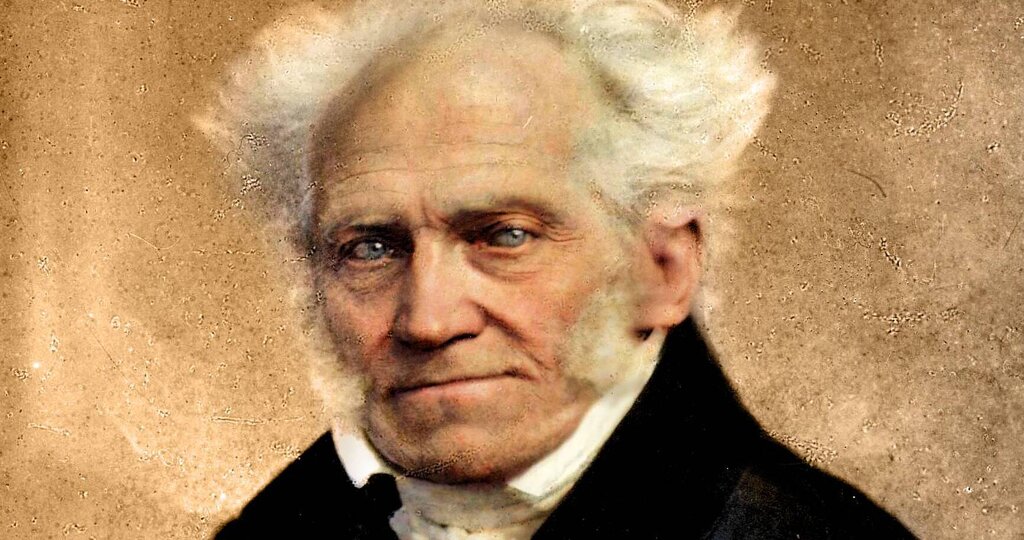

The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer is well known for his defence of solitude; as he said, “A man can be himself only so long as he is alone; and if he does not love solitude, he will not love freedom, for it is only when he is alone that he is really free.” Distinct from loneliness, which stems from not having a rich inner life (according to Schopenhauer), solitude, the German philosopher thought, is essential for developing independent thought, free from outside influences and the superficialities of society.

Based on his own experience, he extrapolated that solitude is essential for contentment too: “Genuine, profound peace of heart and perfect peace of mind, these highest earthly goods after health, are to be found in solitude alone…. And if our own self is great and rich, we enjoy the happiest state that can be found on this miserable earth.” He said, “Were I a King, my prime command would be – Leave me alone.” This does read like the confessions of a curmudgeonly introvert, weary of the world, who wants to be in their own space, away from society, and without interference from others.

But it was not just solitude that Schopenhauer appreciated, but quietude as well. He always opted to live on his own (besides his beloved poodle, Atma), but he bemoaned being subject to the various noises produced by others and society. He found this got in the way of his thinking: “noise is the most impertinent of all interruptions, for it not only interrupts our own thoughts but disperses them.” He took particular issue with the cracking of whips coming from horse carriages on the streets outside:

But to pass from genus to species, the truly infernal cracking of whips in the narrow resounding streets of a town must be denounced as the most unwarrantable and disgraceful of all noises. It deprives life of all peace and sensibility. Nothing gives me so clear a grasp of the stupidity and thoughtlessness of mankind as the tolerance of the cracking of whips. This sudden, sharp crack which paralyses the brain, destroys all meditation, and murders thought, must cause pain to any one who has anything like an idea in his head. Hence every crack must disturb a hundred people applying their minds to some activity, however trivial it may be; while it disjoints and renders painful the meditations of the thinker; just like the executioner’s axe when it severs the head from the body. No sound cuts so sharply into the brain as this cursed cracking of whips; one feels the prick of the whip-cord in one’s brain, which is affected in the same way as the mimosa pudica is by touch, and which lasts the same length of time. With all respect for the most holy doctrine of utility, I do not see why a fellow who is removing a load of sand or manure should obtain the privilege of killing in the bud the thoughts that are springing up in the heads of about ten thousand people successively. (He is only half-an-hour on the road.)

Hammering, the barking of dogs, and the screaming of children are abominable; but it is only the cracking of a whip that is the true murderer of thought. Its object is to destroy every favourable moment that one now and then may have for reflection.

The idea of the sound of the whip cutting into one’s brain feels relatable; I often feel this kind of sensitivity. If an upstairs neighbour drops something, I wouldn’t say it’s extremely loud, but still, the sound ‘gets into my brain’, in the way Schopenhauer describes. Even if I were out in the city where there are much louder noises, the noises kind of mesh together in a big cacophony of sounds (which isn’t to say this doesn’t also get overstimulating and tiring as well), yet quiet interrupted by a sudden noise has more of a jolting effect. (The discomfort created by the noise of others is expressed through the genre of psychological horror in Roman Polanski’s 1976 film The Tenant.) I can relate to Schopenhauer’s annoyance. What he desired, which he argued others also needed for concentrated and productive thinking, is quiet solitude. Indeed, true solitude is not just being on one’s own but free from noise, so that one is truly left alone with one’s thoughts.

However, as much as Schopenhauer praised the virtue of solitude, he was not blind to the dangers of it, namely, its excesses. I came across this other perspective from him in David Bather Woods’ brilliant new biography of Schopenhauer: Arthur Schopenhauer: The Life and Thought of Philosophy’s Greatest Pessimist. Woods writes that Schopenhauer realised that an “adverse effect of excessive solitude is a painfully heightened social sensitivity when compelled to stand in the company of others. Those who are well accustomed to socializing, by contrast, seem to develop thicker, more protective skins.” As Schopenhauer himself stated:

[O]ur mind becomes so sensitive due to its constant seclusion and loneliness that we feel worried or insulted or hurt by the most insignificant incidents, word, or even mere facial expressions, whereas those who are constantly in the thick of the fray do not even notice such things.

Amongst all the insights contained in Woods’ biography, this insight into excessive solitude probably stood out to me the most. I find it extremely relatable, and it made me reflect on the relationship between solitude and social anxiety, how they (can potentially) feed into each other, creating feedback loops, where excessive solitude breeds social anxiety, the latter of which encourages a stronger motivation to be alone. After all, if the company of others causes so much anxiety, then it must be better to be alone, which, in turn, makes socialising more difficult the next time around. I think the COVID pandemic exemplified this insight from Schopenhauer: re-entry into ‘normal’ society, after lockdowns and restrictions were lifted, was, for many, fraught with anxieties. Being accustomed to so much solitude, as well as messages about being cautious around others – with a need to physically distance from them – made socialising feel unnatural, awkward, and uncomfortable for a while. Social skills felt impacted. And perhaps for some, these effects still remain.

Pre-pandemic, socialising was more easy-going for many people, whether it was with new or familiar people. Feeling more socially anxious post-pandemic might not be solely related to the pandemic, or related to it at all. But it’s also understandable if it’s been partly or mainly the cause of heightened social anxiety for some people: being trained to view solitude as ‘safe’, and others as ‘risks’, could create a default guardedness, stand-offishness, and social discomfort (of course, some people, due to personality and mental health factors, are more susceptible to this than others). Indeed, many people with social anxiety report that their symptoms got much worse as a result of the pandemic.

Schopenhauer himself lived through a cholera outbreak, after which he spent the remainder of his life living in relative isolation; so perhaps he too (partly) grew accustomed to solitude and avoidance of others, due to this epidemic. Yet, Schopenhauer’s point about excessive solitude extends beyond the isolation and anxieties brought on by epidemics and pandemics. Modern society also makes excessive solitude more likely and easier, through the internet, social media, parasocial relationships, living vicariously through others, and working from home. As someone who works remotely full-time, it is very easy to spend too much time alone. I often value the solitude – as it allows me to get through the films on my watchlist – but I also know that if I don’t force myself to go out, which means resisting giving in to my excuses and reasons not to, then I can easily spend multiple days on my own without having a proper conversation with anyone.

The quote from Schopenhauer on excessive solitude made me think about how, the more time I spend with people, the thicker my ‘social skin’. Whereas, when I spend much less time with others, it’s easy to see how this leads to a thinner social skin, and so, as Schopenhauer observed, social interactions are marked by greater overthinking, overanalysing, worrying – in the moment and later on – about what I or others have said or done. Being sociable is not, unfortunately, a set-in-stone capacity, which doesn’t change once developed. It fluctuates. Without regular social interaction, sociability and comfort around others weaken. This is why Schopenhauer recommended that any young person who, like him, is solitary by disposition should be reluctantly sociable:

Someone who, particularly during his early years, is unable to endure for any length of time the barrenness of solitude, as often as the justified dislike of people may have driven him into it, this person I advise to become accustomed to carry a part of his loneliness with him in society, hence to learn even in society to be alone to a certain degree and not to tell others immediately what he is thinking and, on the other hand, not to take too literally what they are saying…. Then he will not quite be in their company, although he is in their midst.

While this might be preferable to excessive solitude, this recommendation does, to my mind, increase the risk of loneliness (since Schopenhauer is recommending that this person holds back what they think – who they are, in other words – and instead keeps their distance when with others). This kind of loneliness, to feel lonely around others, can be a painful feeling, so I’m not sure if Schopenhauer’s advice would have the intended effect, that is, to stave off the pain of loneliness. As Woods notes, “it sounds like an unhappy compromise. In fact, it sounds like a heartbreakingly lonely way to live: those qualities of yours that people are bound to find unlikeable, try in future just to keep them to yourself.”

There is a cynicism and misanthropy in Schopenhauer’s advice; he is generalising what all people are like – how they would all react negatively to the naturally solitary person’s sincere thoughts and qualities. His advice also seems to be unmistakably based on his own life experience: his mother Johanna and others directly expressed to Schopenhauer how they found his personal qualities unlikeable. (One letter from Johanna to her son is well known for its stinging attack on Schopenhauer’s character, such as his know-it-all attitude.)

Schopenhauer’s cynicism and misanthropy, like cynicism and misanthropy in general, can act as a protective mechanism, saving oneself from being further disappointed by others. By assuming the worst in people and avoiding opening up, you can somewhat avoid being hurt – but this doesn’t avoid the costs of isolation and negative emotions that come with this. Reading Woods’ biography, it became clearer to me how many of Schopenhauer’s strong generalisations were based on his own personal experience. This doesn’t necessarily make those generalisations wrong, but when they do seem too strong, lacking in nuance, or just easy to find counterexamples to, it does make me think Schopenhauer was not as self-aware or wise as I imagined him to be. In the case of his advice to be reluctantly sociable at a distance, as well as his disdain for others, he doesn’t seem to recognise the limits of his advice – how it may feel like a suitable coping mechanism for him, but not apply to others. (Woods’ biography offers other insights into how Schopenhauer’s personal life mixed with his philosophical views in all sorts of unique ways, such as his views on suicide and madness: his father died by suicide, and he made multiple visits to an asylum.)

Personally, I don’t view the solution to excessive solitude – as someone who appreciates solitude – lies in treating others and a social life as a chore, something to put up with, as a means only to my own ends (i.e. staving off painful feelings of loneliness). A social life (with the right kind of people) does help to avoid loneliness. But Schopenhauer’s view of a social life (which, after all, was influenced by the kind of society he lived in, and the people he was accustomed to) seems reductive, too black and white, too personal. Better company is a better solution than reluctant and stand-offish socialising. One can avoid the pitfalls of excessive solitude that Schopenhauer drew attention to without viewing others as the mere alleviation of one’s loneliness.

When someone is treated as a whole, unique individual – who we may connect with in an unexpected way, if we let ourselves be authentic – this is often a better solution than pre-judging people and social interactions in a negative, reductive, and simplistic way. Schopenhauer may have fallen prey, to use Martin Buber’s language, to ‘I-It’ relationships, rather than ‘I-Thou’ relationships, viewing others as for his own use and analysis, which is a barrier to meaningful connection.

It’s important to recognise, as perhaps Schopenhauer didn’t do enough, that one also has to be good company oneself. We all have a unique mixture of virtues and vices, as Schopenhauer did, but sometimes certain vices, which we can change, get in the way of a rich and fulfilling social life. Being bitter, arrogant, argumentative, self-aggrandising, or harsh towards others is unpleasant. A healthy amount of solitude should encourage greater introspection into oneself – into qualities that are, in fact, character flaws, and which hinder our ability to connect with others. Avoiding loneliness, then, involves not simply spending more time with others; it also means reflecting on one’s own traits, insecurities, and defences that may be frustrating more meaningful relationships.