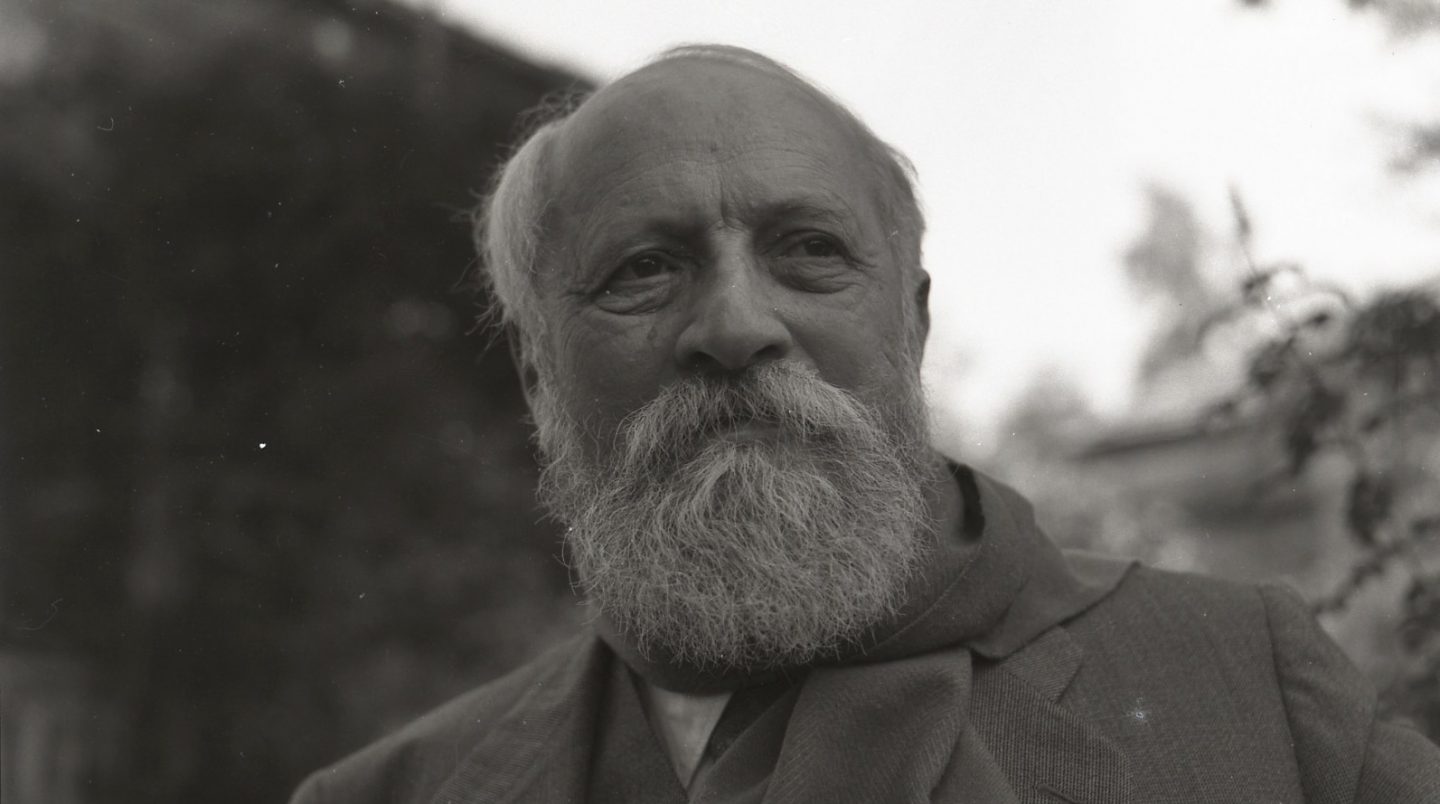

I first heard about the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber (1878–1965) and his book I and Thou (1923) from a therapist I used to see. I remember that out of nowhere and for a period of several weeks, I was feeling unusually elated and blissful, and I would have (what felt like) these very deep and meaningful experiences when with people and making eye contact. I described these experiences to my therapist, which made her mention Buber’s dialogical I-You (or I-Thou) relationship. It was years later when I decided to actually read I and Thou, and while many passages feel cryptic, unclear, or ambiguous, reading this book has helped me to make sense of those unusual moments of human connection.

I would agree with Buber that the I-You relationship can be rare and fleeting, but that they are a source of meaning, although Buber views them as our ultimate meaning. Towards the end of the book, he states that this “essential act of pure relation”, this relationship of reciprocity and mutuality, makes life “heavy with meaning”, that it is “the inexpressible confirmation of meaning,” “nothing can henceforth be meaningless,” and “The question about the meaning of life has vanished.” It is an ineffable meaning, one which we “lack any formula or image for”, but which is “more certain for you than the sensations of your senses.” Buber additionally links I-You with the feeling of freedom. Indeed, when we shift to this orientation, this way of being with others, we are free of alienation and we experience the freedom of our being.

There is also a mystical quality to these types of associations or encounters with others, similar to the mystical experience of being in relation to what people call God, which Buber calls the ‘Eternal You’, which is the You (or Thou) that can never become an It, the presence which we can gain knowledge of through our relations with human presences, for example. We can, however, have an encounter with the Eternal You, not just people and nature which give us intimations – glimpses – of the Eternal You, if we ready ourselves for it – we have to want such an encounter to occur, which Buber calls “man’s decisive moment.”

Buber’s description of the I-You relationship, be that with another person or God, reads very much like accounts of mystical states, which have these ineffable and noetic qualities, often accompanying encounters with a presence, force, or being that is felt to be divine or sacred, and which invokes awe and reverence. The I-You relationship one has to the Eternal You also reminds me of Rudolf Otto’s description of the numinous, which Otto calls the “non-rational, non-sensory experience” of being in the presence of ‘the holy’ – this “wholly other” that is greater than oneself, outside the self, and experienced as mysterious. (See my article on psychedelics and the sublime for a more detailed discussion on this.) I can moreover see connections between Buber’s philosophy and that of the Sufi mystics, who speak of their (the lover’s) direct relation with the ‘Beloved’ (God).

Contrary to the classic account of the mystical experience, as well as many schools of mysticism (i.e. Hindu, Buddhist, Christian, Sufi), Buber rejects the notion of unity being fundamental. His worldview is dualistic since it is based on relation – on two beings in dialogue that cannot ultimately be collapsed into one. In altered states of consciousness, induced by meditation or psychedelics, one may come to the following realisations (through first-hand experience): there is no self, there is a self (known as Atman in Hinduism) but it is the same as ultimate reality (what Hindus call Brahman or the Supreme Self), and unity is elemental.

Yet Buber considers these “doctrines of immersion” to be delusions (‘immersion’ could also be rendered as ‘meditation’). He criticises what he believes to be the aim of the Buddha and mysticism more generally: “the annulment of the ability to say You”, which involves the psychologisation of the world and God, where both the world and God come to exist in the self. The crucial mistake, herein, is that this rejects the duality – the relation of man to the world and man to God – that Buber sees as being irreducible and ineliminable. ‘Spirit’, Buber argues, occurs “between [emphasis added] man and what he is not,” not in the individual.

Buber is not opposed to meditative concentration, as is practised by mystics belonging to various schools; he actually believes this prepares one for an encounter with the transcendent Other. As he writes: “Concentrated into a unity, a human being can proceed to his encounter – wholly successful only now – with mystery and perfection. But he can also savor the bliss of his unity and, without incurring the supreme duty, return into distraction.” In other words, the unification of the self should not be the endpoint. If you merely remain in that state, according to Buber, you are annihilating the truthfulness of dual awareness for the sake of an illusory non-dual awareness.

The moments of I-You association, Buber says, are pure, direct relation, where you enter into a dialogue, a conversation, communication, with your whole undivided and unique being. It is one presence addressing another presence, in the here and now. The ‘You’ of a person is, and can only be, the presence of uniqueness and wholeness in a person. You can think of this kind of relationship as making you fully human since it involves your whole being and dialogue with your whole being and the other person’s. This genuine dialogue, in Buber’s existentialist philosophy, is the fundamental drive that humans have.

Contrasted to authentic dialogue or meeting is when we experience or use another person, the latter being the I-It relationship that Buber talks about, which makes up the bulk of how we relate to others, not just people, but also non-human animals, the wider natural world, and even God. A tree, for example, while usually an ‘It’, can become a ‘You’ that one addresses. Buber uses the term ‘theomaniac’, similar to egomaniac, to describe the person who turns God into an It, who is obsessed with his or her personal relationship with God, rather than treating God as the Eternal You.

The I-It relationship is focused on conceptualisation, manipulation, and accumulation. It takes form when we are assessing others, turning them into objects, and trying to gain something from them. “What can you do for me?” would be an attitude characteristic of the I-It relationship. This relationship is one-sided and centred on utility or control, perhaps even indicative of the will to power that Nietzsche opines as being the basic human drive and which he venerates, contrary to Buber’s worldview. According to Buber, such a way of relating produces a sense of meaninglessness, alienation, and oppressiveness. We do not experience true freedom, the freedom of our being, in these instances. However, Buber is not saying we should discard I-It relations, for we need them to function in the world; however, his book does aim to celebrate the I-You relationship. Buber mourns just how pervasive and saturated I-It relations are in our lives and the loss of meaning and joy this entails.

When we find ourselves locked into the I-You relationship, the experience feels ‘right’ and deeply intimate – what we have been yearning for, and what makes us fully human. But whether your relationship is of the I-It or I-You type, the I does not exist by itself: there is, Buber argues, “only the I of the primary word I-Thou and the I of the primary word I-It.” I can definitely appreciate this relational view of the self, that the ‘I’ never exists in isolation, only in relation to others. And to Buber, this ‘I’ has a twofold nature, in accordance with the twofold attitudes we can take towards the world, or the two basic word pairs: I-It and I-You. The ‘I’ of the former is not like the ‘I’ of the latter.

We do not enter into an I-You relation through an act of will, but through “grace”, in Buber’s eyes. We cannot force it to occur. Nevertheless, we have to be open to these moments and choose to enter them. He writes that “if will and grace are joined, that as I contemplate the tree I am drawn into a relation, and the tree ceases to be an It. The power of exclusiveness has seized me.” We have the decision to respond to a call. And so even if we cannot make our lives more concentrated with I-You relations through sheer will alone, we can see the importance of such associations and thus be more open to them, which can help in terms of their actualisation.

I think I will need to read some other sources and interpretations of this philosophy to better grasp it, but I will say that Walter Kaufmann’s prologue and notes, and Buber’s afterword, were still very helpful in clarifying the ideas behind this original, dialogical, and mystical brand of existentialism.

Hi Sam, I have been trying to find a quote you give, I have no idea which version of I and Thou you refer to, and which translator, but it’s this ““essential act of pure relation”. Can you help? I have been looking at so many version but cannot find it. Thanks.

Author

Hi Shelley. My copy is the Walter Kaufmann translation, with the prologue by him. The phrase is here if you do a keyword search:

https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/martin-buber-i-and-thou?v=1619970582