When it comes to looking after one’s mental health, there is no guarantee what kind of treatment will offer relief and the stabilising effects to get on with one’s day-to-day activities. This is why itis paramount to exhaust all the options available. One approach and method of psychotherapy may work for one individual but not another. And the same applies to medications.

However, self-care is by no means limited to talking and pills. What also needs to be emphasised are the lifestyle changes which are effective for ameliorating mental health conditions, such as depression.

Dr Stephen Ilardi, a professor of clinical psychology, has developed a 6-step programme to beat depression without the use of drugs, and it involves physical activity (exercise), omega-3 fatty acids,

sunlight, healthy sleep, anti-ruminative activity, and social connection (links are included with studies supporting each recommendation).

However, there is perhaps another lifestyle change that Illardi should recommend. The effect of diet on mental health should not be underestimated, and although Illardi highlights the promising improvements to depression influenced by omega-3 fatty acids, there is also good reason to look after your gut. We keep finding out how the gut plays a surprisingly impactful role in our moods.

Healthy Gut, Healthy Mind

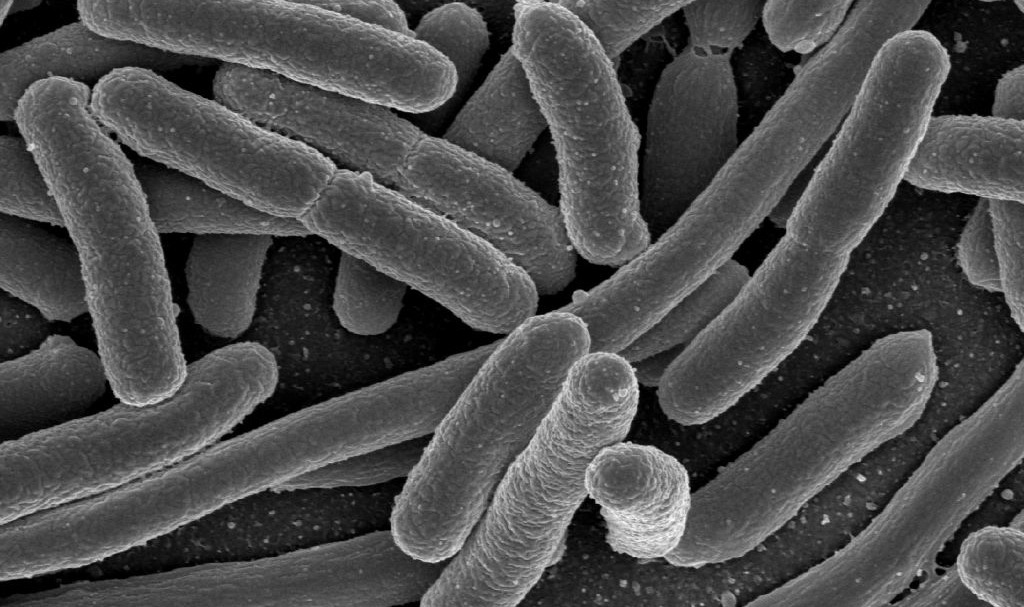

The human microbiome is made up of trillions of microscopic organisms (microbes) that live in the human body. These microbes – including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and even microscopic animals – live all

over our body. 95% of these organisms live in our gastrointestinal tract (gut), and the combination of these microbes, their genes, the environment they inhabit, and the material they produce, is known as the human microbiome.

Our microbiome has been linked not just to our physical health (and being implicated in a number of health afflictions) – it is intimately tied to our mental health as well. By means of the gut-brain axis, the bacteria in the gut can send and receive signals to and from the brain. There are numerous studies highlighting how the communication between the gut and the brain impacts our well-being. For example, one study found that the addition of a ‘good’ strain of the bacteria lactobacillus (found in yoghurt) to the gut of normal mice reduced their anxiety levels. Moreover, this effect was blocked when the connection between the gut and brain (the vagus nerve) was cut. Thus, a regimen of yoghurt may help people suffering from anxiety to minimise their symptoms.

Research also shows that when germ-free rats were transplanted with the microbiota of major depressive disorder patients, this created depressive-like behaviours, whereas transplantation of the microbiota of healthy controls did not induce such behavioural changes.

A fascinating new study found that gut microbes seem to influence microRNAs (miRNAs) in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex of mice. These biological molecules control how genes are expressed in these brain regions, and their dysfunction is believed to contribute to psychiatric disorders. Researchers learnt that a significant number of miRNAs were altered in the brains of microbe-free mice. These mice displayed abnormal anxiety, depressive-like behaviours and deficits in sociability and cognition. However, adding the gut microbiome later in life normalised some of the changes to miRNAs in the brain. If findings from studies like these can be applied to humans, then this could open up a novel approach for the treatment of depression, by modulating the miRNA in the brains of people with psychiatric disorders, for example.

We have known for some time that stress contributes to the onset of mental illness, but what we have discovered more recently is how this can occur – in other words, what the link is. A study has shown that minor changes in mice microbiota induced by neonatal (newborn) stress can lead to anxiety and depression-like behaviour in adulthood. It’s important, however, to find out whether these results also apply to humans, by establishing whether patients with anxiety and depression disorders have abnormal microbiota profiles.

What Should You Do With This Information?

Using interventions targeted at the gut to treat mood disorders (known as ‘psychobiotics’) is not clearly supported by the evidence available. For instance, a systematic review underscored that a majority of people taking probiotics (live bacteria – found in yoghurt, kefir, sauerkraut, tempeh, kimchi, miso, kombucha, pickles and natto) did not experience any changes in mood, stress or symptoms of mental illness. On the other hand, there are very few studies with humans, whereas studies with mice show that probiotics reduce the stress hormone cortisol, and decrease anxiety and depressive behaviours.

Numerous studies show that people who eat a high-quality, balanced diet have lower rates of mental illness. Clearly, diet affects gut microbiota, but more research is needed on the link between healthy gut microbiota and mental health. In the meantime, personal experimentation with gut-friendly foods can’t do any harm – and may offer benefits that no other therapeutic, medicinal or lifestyle change has so far led to.

Evidence-based ways to improve your gut microbiota include eating a diverse range of foods; eating lots of fruits, vegetables, legumes and beans; eating fermented foods; avoiding artificial foods; eating prebiotic foods; eating whole grains; eating a plant-based diet; eating foods rich in polyphenols; and taking a probiotic supplement.