Asylum designs in the 19th century were believed by medical practitioners, psychiatrists, and asylum architects to ameliorate, if not cure, madness. (In this essay, I will use the term ‘madness’ instead of mental illness because as sociologist Andrew Scull highlights, “for much of history, “mad” or some cognate of it really was the word that was used.” So its use here will be in keeping with its historical context and is in no way meant to validate its stigmatising or derogatory connotations.)

The following discussion will focus on 19th-century asylums, yet due consideration will also be given to asylums built before this time period and the decline of the asylum in the 20th century. This wider historical context will help to elucidate exactly how the design of asylums served to ameliorate madness and to what extent. By looking at Thomas Kirkbride’s highly influential asylum plan, as well as historical examples of asylums and the ideas behind them, I will argue that the design of 19th-century asylums helped ameliorate madness due to two important factors.

The first factor, which will comprise the first section of this discussion, involves the architecture, structure, and arrangements of the actual building. The second factor, which will take up the second section of the discussion, involves the practice of ‘moral treatment’. It should become clear that the building itself, and the practices upheld within it, were both interdependent and mutually worked together to ameliorate madness. I will stress throughout the discussion that the architecture of the asylum helped ameliorate madness by giving order and comfort to patients, while moral treatment acted as a superior method to physical restraint because it treated madness as a mental problem, and not a physical one.

Moral Architecture and Features of the Building

Moral Architecture

Since madness was generally seen as a problem needing moral and emotional treatment, instead of physical treatment, the architecture of asylums increasingly focused on encouraging moral treatment. There was, as Lu Ann De Cunzo puts it, a moral architecture to the building. The structure of the physical building was intended to affect the structure of the mental lives of patients. This notion that one’s environment, such as the design of an asylum, can shape behaviour has also been called environmental determinism by some and it was largely through this assumption that madness could be better alleviated.

If, for example, the design of the asylum could dissociate the patient from the life experiences that caused their madness, then their sanity could be restored. The idea that the building itself could have a curative effect is not just an idea held by historians of psychiatry but was strongly believed by 18th-century asylum physicians as well. As a case in point, William Battie wrote in his Treatise on Madness that a design that promoted confinement would have a positive effect on patients. Yet, even though the notion of moral architecture was gaining popularity in the 18th century amongst many head physicians, it was not until the 19th century that physicians paid close attention to the physical design of the asylum. In order to convey how effective 19th-century asylums were in ameliorating madness through their design, it will be worth focusing the discussion on some important features of these asylums.

Features of the Building

The location of the asylum was a crucial factor in the patient’s recovery. Kirkbride notes in his asylum plan that any asylum “should be in the country, not within less than two miles of a town”. This is to ensure that all the necessary supplies and services can be easily obtained, which will further ensure the maintenance of the asylum, and therefore the maintenance of the patients. Kirkbride goes on to add that the country should be “healthful” and “pleasant”, with the surrounding scenery being “attractive”.

These aesthetic considerations were based on the observation that “the insane were very sensitive to their surroundings”; and so details, like the location of the asylum, were able to contribute to the mental well-being of the patient. The surrounding landscapes were able to affect patients in this curative fashion because, in the words of Susan Piddock, “they were vested with symbolic meaning” and it was the symbolic meaning of the surroundings, and not necessarily the surroundings themselves, which helped to ameliorate madness. This point also ties in with the claim that madness was a mental condition in need of mental, not physical, treatment.

On the question of size, Kirkbride explicitly states that the asylum should be moderately sized and hold no more than 250 patients. A building any larger would mean that it would be difficult for a few attendants to constantly survey many patients, as was the case with the Bethlem Royal Hospital whose overall length was 580ft. A large building would also make it difficult for the chief medical officer to visit every patient on a daily basis. Luther V. Bell stressed that in a moderately sized hospital the superintendent is able to personally track the progress of each patient. Arguably, this would make their recovery (or at least alleviation of their symptoms) more likely. A further problem with an institution too large is that improvements would become too costly. So, in order to ensure the efficiency of the asylum, and therefore the efficiency of the patient’s recovery, the size of the building had to be carefully thought out.

The architect Robert Reid believed that the subdivision of space within the asylum, and the subsequent categorisation of patients, helped to ameliorate many different kinds of madness. More generally, the ordered and structured placement of wards was supposed to improve the disordered and unstructured passions of the inmates. Kirkbride’s design conformed to Reid’s ideas and included plans of a centre building with wings on each side, the wings then being divided into wards for eight classes of patients. Kirkbride argued that “highly excited or violent patient[s]” should be separated from the more timid patients. This was because any disruptions in the asylum were likely to cause discomfort to the more quiet patients and therefore prevent their return to a state of sanity. The Alabama State Hospital (1852) kept well-behaved patients close to the centre and the more noisy patients in the outermost wards on this basis.

On the distinction between ‘curables’ and ‘incurables’, Kirkbride’s plan explicitly points out that neither group should be separated. Since it was always possible that the ‘incurables’ could be cured, separating them would be “dooming [them] to hopelessness”, according to Kirkbride. The separation of sexes was also important. The reasoning behind this was that if the sexes were allowed to mix, strong intimacies may form; intimacies which may be dangerous “…to a sensitive mind after a complete recovery”, as Kirkbride said. To guarantee this separation, some 19th-century asylums required that the men’s view of the women be “blocked by means of walls and shrubbery”.

According to Andrew Scull, the most frequently used asylum design, in England at least, “was the corridor type”. With an asylum being mainly made up of long corridors, there are two ways in which this can have a curative effect on patients. Firstly, the use of corridors made surveillance of patients a lot easier. This meant that suicidal patients could be watched more closely and any self-destructive behaviour could easily be prevented. The second way in which the long corridors helped ameliorate madness was due to the way in which they allowed the patients to stroll in a setting similar to the corridors or ‘galleries’ of country houses. This design feature helped to ameliorate madness because patients found themselves in a spacious, domestic environment that gave them a great deal of comfort. There are also many other design features that aimed to ameliorate madness by way of creating a comfortable, domestic environment.

Kirkbride suggested that the floors of the asylum should be made of “seasoned wood” in order “to prevent the transmission of sound”. The reasoning behind this requirement is that the quiet atmosphere of the asylum would find its counterpart in the serenity of the patient, alleviating any disturbances in their minds. Dr W.A.F. Browne noted in 1837, in agreement with the Kirkbride plan, that “sun[light] and the air…[should]…enter at every window”. Ample ventilation and natural lighting was needed in order to create a pleasant setting. Such design features, as exemplified by the Derby County Asylum (1844), were seen as ameliorating madness more effectively than the prison-like attics of the Bethlem Royla Hospital.

To guarantee the safety of the patients, and therefore prevent any traumatising or painful accidents which could exacerbate their madness, “the [asylum] should be made as nearly fire proof as circumstances will permit”, as Kirkbride stresses. To be mentally healthy, patients had to be physically healthy – this was why separate infirmaries were also commonly built to prevent infectious diseases from spreading. To further ensure the physical well-being of the patients, and their comfort, asylums were supposed to have an abundant supply of water. An abundant supply of water meant cleanliness and hygiene could be achieved through the extensive use of baths and washrooms. Robert Gardiner Hill (of the Lincoln Lunatic Asylum) also underlines that this feature of any asylum would make it “scarcely possible for [the patients] to suffer from thirst”. Other design features, such as clean, odourless toilets and generous heating, also contributed to the cleanliness and comfort of patients as a way to ameliorate madness.

There is one last physical aspect of the asylum I want to consider. It involves the aesthetic features of the asylum and the way in which they served to comfort and soothe patients. Henry Burdett was of the opinion that “in the best English asylums the furniture must resemble that of a private house”. Having beautiful and comfortable furniture to sit on, as well as vibrant decorative flowers (as the Sussex Asylum was known to have), states of stress and depression, which contribute to madness, could be soothed.

Kirkbride certainly believed decorative features could have this positive effect when he wrote that “a painted or simple stout muslin verandah awning over each window”, in the asylum, “will be found to add much to the comfort of the patients”. This discussion of the physical features of the asylum has hopefully clarified how the design of the 19th-century asylums conformed to the idea of moral architecture and aimed to ameliorate madness by way of comforting patients in a domestic environment. But, the practice of moral treatment was also outlined in asylum designs as a way of remedying madness, so it is important to take this practice into account.

Moral Treatment in Asylums

Work and Leisure

Moral treatment was an approach to treating mental disorders in a humane and compassionate way, which involved teaching patients to be disciplined as well. Moral treatment was upheld within the asylum by giving patients work to do and leisurely activities to enjoy – both of which also depend on some physical features. For example, Kirkbride proposed in his plan that some sort of farm building should be built. Inmates would be able to work in this building, either by growing crops for the hospital or tending to the farm animals. Occupying the patients with work was unique to 19th-century asylums – critics accused earlier asylums “of being dens of idleness” (Roy Porter, Madness: A Brief History).

For Robert Gardiner Hill, when the inmates engaged in outdoor employments or workshops this gave them “vigour” to an otherwise “shattered mind”. Physical labour and exercise, as well as academic learning, were effective in ameliorating madness because they created order in the daily lives of patients. This sense of order helped to improve the disordered minds of the mentally ill. In addition, sticking to a tight, ritualised schedule of work and exercise also gave patients a sense of self-control, a feeling that was supposed to be very therapeutic.

Asylums in the 19th century offered many leisurely activities to patients as well. A patient from the Lincoln Lunatic Asylum reported that to be able to “walk in the gardens twice a day and [have] cards to play” was conducive to his well-being. Other activities that worked to make the patients cheerful and ameliorate their madness included listening to music, acting in plays, being able to reflect in beautiful gardens, talking to attendants and other inmates, worshipping in a detached chapel, and even enjoying trips around the countryside, and in town, for the well-behaved patients.

These activities were partly therapeutic for the same reason that certain physical features of the asylum were therapeutic: they gave patients a feeling of comfort and ease. But they also served to divert the patients’ attention away from any emotions that may result in a “paroxysm of grief or an outbreak of violence”, according to Kirkbride; or any disconcerting thoughts that may exacerbate their madness. Life for an inmate in a 19th-century asylum seemed to be a home away from home. To help create this kind of environment, asylum plans also paid close attention to how asylum workers should behave towards the patients.

The Methods of Asylum Workers

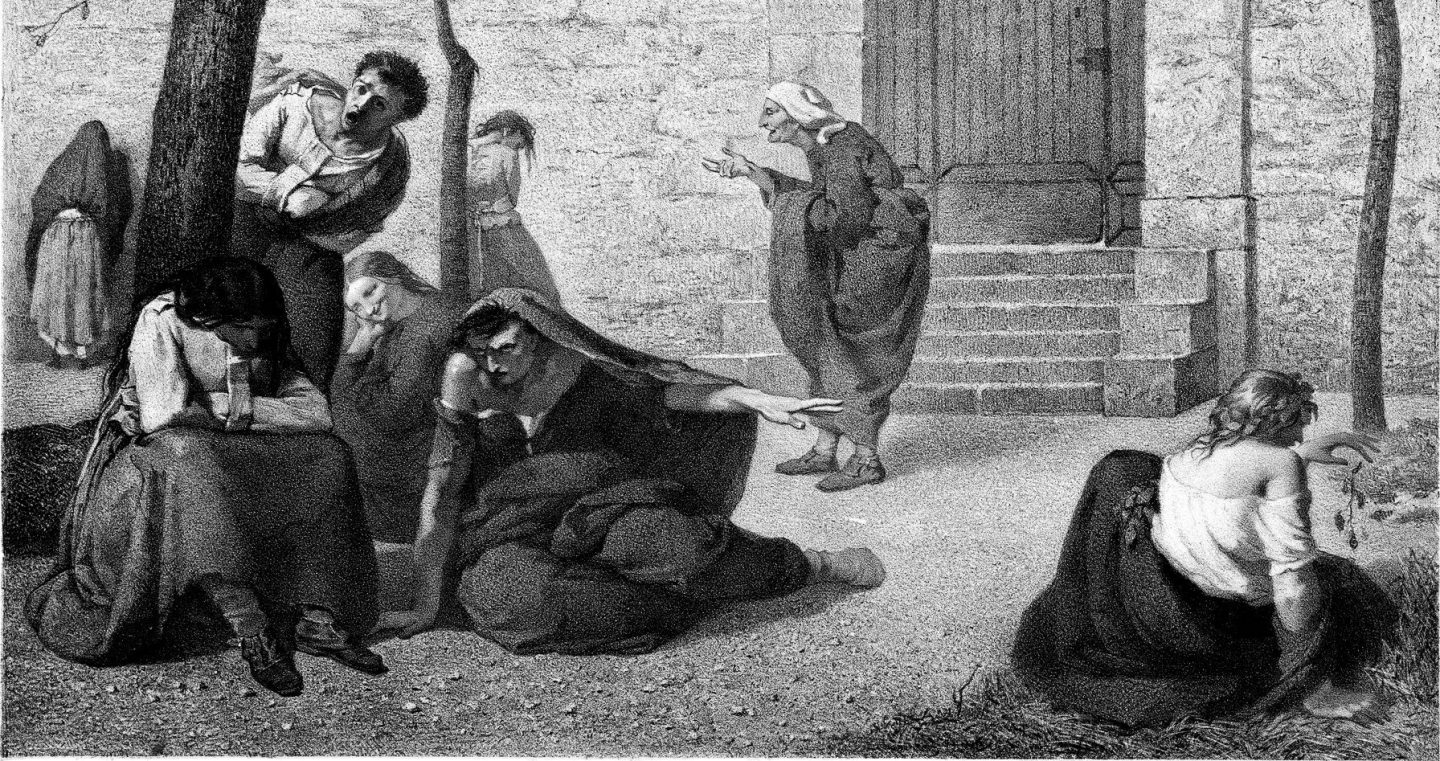

Asylums in the 19th century differed from many previous asylums that allowed attendants and physicians to use physical force and restraint as a means to ameliorate, or at least control, madness. Take the case of inmates at the Bethlem Royal Hospital. They were treated like wild beasts. Other than being physically restrained, by means of irons, manacles, cuffs, and straitjackets; inmates at Bethlem were also subject to cruel methods of ‘treatment’ that included bloodletting, purges, starvation, whipping, and vomits.

Critics of these methods found them to be not only ineffective at ameliorating madness, but dehumanising as well. An alternative method, known as moral treatment, became widespread in the 19th century as a response to the use of physical restraint. In the Kirkbride plan, asylum workers are vested with no powers to use physical restraint as a form of treatment. Instead, we find that the various workers should be cheerful and gentle with the inmates – in the case of supervisors, they should possess moral virtues such as benevolence, sympathy, and kindness.

Most asylum plans, including Kirkbride’s, mention that the physician should be extremely well-educated, especially in medicine and physiology, in order to deal with the varied conditions of the patients. Kirkbride’s plan, which favours non-restraint and non-coercion as well, can find its justification in the works of Phillipe de Pinel and Dr Vincenzo Chiarugi. For example, in On Insanity and Its Classification, Chiarugi champions the view that it is a “medical obligation to respect the insane individual as a person”. And in Pinel’s Treatise on Insanity, it is argued that physical restraint is pointless because if madness is a mental disorder, then it has to be relieved through mental approaches. Kirkbride’s various design features are supported by Chiarugi and Pinel’s demands on how to effectively ameliorate madness. By wanting teachers to promote the happiness of patients, or for the night watch to comfort the more restless patients, we can see that Kirkbride viewed each patient as a person in need of moral treatment.

As previously mentioned, moral treatment included not only treating the insane humanely but also with discipline, since this was the only way inmates could learn to control themselves. Jacob van Deventer (of the Meerenberg Asylum) proposed that nurses should possess characteristics such as “refinement…decency and punctuality” in order to instil a kind of caring discipline aimed at improving the mind of the patient. In the case of The York Retreat (1796), patients were able to gain self-control by way of receiving rewards (such as living near the centre of the asylum) for good behaviour and receiving punishments (such as living in the outermost wards) for bad behaviour. The patient, therefore, had to re-learn how to behave normally and act as a cooperative member in a community. Since the superintendent and her family would also be present in the centre room, they could serve as role models of normal behaviour for patients allowed in this section of the building.

Arguably, the utilisation of moral treatment did help to ameliorate madness. For example, Samuel B. Woodward claimed that his Worcester Hospital achieved a recovery rate of 82-91% between 1833-1845 and Samuel Tuke said in his Descriptions of the Retreat (1813) that his asylum achieved excellent results. But it is important to remember that 19th-century asylums could only ameliorate madness to a certain extent. The eventual overcrowding of these asylums, the over-idealised nature of their designs, and the rise of the use of drugs, led to the decline of the well-designed asylum in the 20th century.

Conclusion

From this discussion, it can be said that the design of asylums in the 19th century helped to ameliorate madness because the architecture of the building comforted the patients and served to structure their daily lives. Asylum designs, like Kirkbride’s, also required that physicians, attendants etc. be compassionate and strict with patients in order to divert them away from the agonising causes of their madness and to give them the power to control their emotions. The architecture of the asylum and the practice of moral treatment upheld within it were interdependent. Together, they were supposed to ameliorate madness in the same way – by affecting the mental experiences of the patients.

The Kirkbride plan was a guide on how to construct and manage a smooth-running, efficient asylum, which could effectively improve the minds of the mentally ill. However, 19th-century asylums were only effective in ameliorating madness to a certain extent. Our understanding of mental illness greatly improved in the 20th century and psychiatrists were better equipped to treat different forms of madness through various medications and different approaches to clinical psychology and psychotherapy.