The ways in which humans stand out from all other species is inexhaustible. Our very psychology speaks volumes about the ways in which we are unique and distinct from other animals. Perhaps one of the most fascinating ways in which humans stand out is to do with this idea of potential.

The uniqueness of human potential is the ability to manifest ideas, motivations and goals. We paint visions, set up projects to save people’s lives and climb to the summits of foreboding mountains. We can overcome both internal and external struggles and make incredible changes in our lives. Other organisms have the potential for growth, in the sense of developing from an immature stage to a mature stage. But human potential is something of a very different order. And it is this basic fact which occupied the work of psychologist Carl Rogers (1902 – 1987).

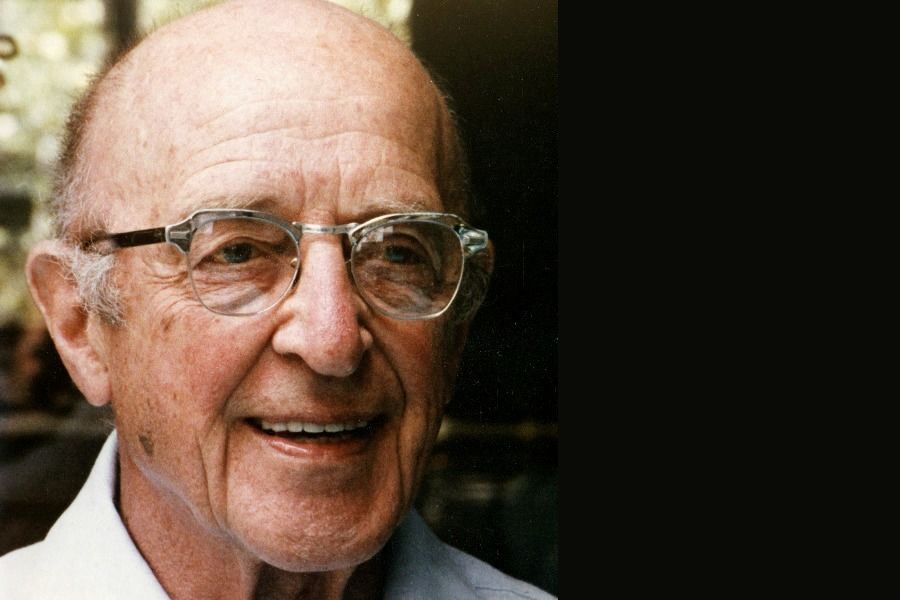

Rogers was an American psychologist and one of the founders of the humanistic approach to psychology, which emphasises the study of the whole person and the uniqueness of each individual. For Rogers, the focus was not on behaviour (Skinner), the unconscious (Freud), thinking (Wundt) or the human brain, but on how each person perceives and interprets events. In his book On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy (1961), Rogers describes ‘the good life’ – the fulfilling, happy life – as a life in which the organism aims to fulfil its potential. Since the humanistic approach focuses on the distinctiveness of each person, potentialities will therefore vary. Moreover, the good life is not a state one reaches, but a process. Roger says:

This process of the good life is not, I am convinced, a life for the faint-hearted. It involves the stretching and growing of becoming more and more of one’s potentialities. It involves the courage to be. It means launching oneself fully into the stream of life.

Indeed, trying to fulfil one’s potential is a process of self-growth, and growth can be arduous and painful in all sorts of ways. The mental anguish can begin just from realising that you have a potential unfulfilled, from the nagging feeling that you could be achieving so much more, but you’re not. Since, according to Rogers, the basic human drive is realising some sort of potential, when we don’t become what we could be, it’s stultifying. How much of our mental distress is really related to potentialities left only as potentialities? Can the burden of regret, emptiness, hopelessness and existential angst be ameliorated by this “stretching and growing” that Roger alludes to?

These are tough questions. But perhaps they can only be answered by experience and action. Whatever abilities, talents, skills, passions and pursuits you have – or weaknesses that you feel are limiting you – there is always a way to ‘push yourself’. Of course, for each person, this push against some weight – seemingly immovable at first – will be a different experience. For one person, the challenge may be striking up conversations with strangers, while for someone else it could be finishing writing a book. Depending on the weight, progress could be slow (or, more accurately, appear slow), while change could happen more radically for others.

This process of becoming who you could be – the best version of yourself – is called self-actualisation or self-realisation. Other psychologists, such as Abraham Maslow, attached great importance to this human need. In his book Motivation and Personality (1954), Maslow said: “What a man can be, he must be.” The crucial first step, though, is trying to figure out what we can be. Then the work can really begin.